RITA’S STORY

I was eleven years old when the Second World War started. Great Britain declared war on Germany on 3rd September 1939. It was a dreadful time but I was too young to fully appreciate that. In due course we were all issued with a gas-mask, which we had to carry with us at all times. They were very hot and uncomfortable to wear, even for a short time, when we had gas-mask practice in school. Thankfully, we never had any Gas attacks. Then, we all had to have ration books, with coupons inside, which had to be handed over in the shops, when you bought food. This was so everyone would get their fair share. Finally, we were all issued with Identity Cards, each with our personal number on it. Mine was SJQA614.….

Here's a photo of a family wearing their gas masks -

I was eleven years old when the Second World War started. Great Britain declared war on Germany on 3rd September 1939. It was a dreadful time but I was too young to fully appreciate that. In due course we were all issued with a gas-mask, which we had to carry with us at all times. They were very hot and uncomfortable to wear, even for a short time, when we had gas-mask practice in school. Thankfully, we never had any Gas attacks. Then, we all had to have ration books, with coupons inside, which had to be handed over in the shops, when you bought food. This was so everyone would get their fair share. Finally, we were all issued with Identity Cards, each with our personal number on it. Mine was SJQA614.….

Here's a photo of a family wearing their gas masks -

Soon men were having to go into the Army, Air Force or Navy, unless

their job was important to the war effort, or their health was not good.

The men from Kirkintilloch where I lived, were all away in other parts

of the country, training for war, while our town was full of soldiers,

in training, from elsewhere, and living in schools, church halls, etc.

Our house over-looked St. Ninian’s School playing-fields, where they had

their physical training - it was called ‘square-bashing’ - and designed

to make them very fit. All this made our quiet little country town a

very different place.

The next thing that happened was that there was a great fear of German planes coming over and bombing our towns. Clydebank was thought to be in danger because of the ship-yards there, so it was decided to move all the children away to a safer place - in this case - Kirkintilloch. Thousands of them arrived in our town, with their mothers, but no fathers - they had to stay and carry on with their jobs. They were brought to the Town Hall, carrying bags with clothing, and with labels pinned on their coats showing their names and addresses back home in Clydebank. The people of the town had to report to the Town Hall to be allocated a child or children. My mother was given a family of three - Peggy was about twelve , Jack ten, and William five years old. We had no spare beds, so my mother put a mattress in a corner of the living-room, on the floor, and all three slept there. After a week, their parents came to visit, and decided to take them back home. What I remember particularly is they had not lived in a house with a BATH before. Gradually, many others went back to Clydebank, as there had been no bombing at that point though some families stayed in Kirkintilloch permanently.

We lived in Northbank Avenue - just a small avenue of six houses, which had all been built by Mr. Fletcher, the local builder. He lived in the largest one, built on a steep hillside, which gave him a big cellar. When war came, he decided to make this cellar into an air-raid shelter, for all the Avenue people, and one other lady. He fitted it out with comfortable seats, a couple of bunks, lighting, heating, tea-making facilities and even a toilet. The air-raid siren was on the roof of the Police Station, in the centre of the town. It made a loud wailing sound, which could be heard for miles, first a warning sound, then the ‘all-clear’ if the danger was past. So, throughout the war, we went to the shelter when the siren sounded, always at night, and having to get out of bed and get dressed. Our house looked away over to Bishopbriggs, where there were anti-aircraft guns, which would fire at enemy planes. You know there is a saying “What goes up must come down“. During air-raids it was unsafe to be out because shrapnel from the guns would rain down - great lumps of jagged metal - these would be lying about the streets the next morning. I wish I had kept some, just for interest. I never knew of anyone getting hurt by the shrapnel, but my father’s friend had a pony and trap, and a piece came through the roof of the shed and killed the pony. In 1941 Clydebank was bombed two nights running, 439 planes came over and dropped 1000 bombs. The town was a ruin, lots of people killed. Kirkintilloch Fire Brigade went to help put out the fires, some of which still burned after a fortnight. Grandpa Green’s father was a bus-driver at the time. And driving in that area. One bomb went down the funnel of a ship lying in the Clyde - but it didn’t explode. Of course, we were lucky to be safe in our shelter, but no sleep for the noise of gun-fire etc.

[John adds: “One of our uncles, a joiner to trade, was a part-time member of the local Fire Brigade at the time of the Clydebank blitz. He couldn’t cope with what he saw there, and that was the end of his time in the Fire service.”]

[John adds: "Jean my wife lived near the docks in Glasgow and remembers the night the bomb went down the ship's funnel. She had been evacuated, but this was one of the occasions when she was spending some time at home. The whole area had to be evacuated, and she and her family spent the night in a close in Sauchiehall Street opposite Kelvingrove Park."]

Then there was the BLACK-OUT, no lights allowed to shine out of windows or doors, everywhere heavy curtains drawn at night, and NO STREET LIGHTS, can you imagine it? Cars had very faint lights that would not be seen from above, by planes, and no name signs on roads.

Just learned this very interesting fact recently from a booklet John gave me.

The Fletcher home, at No. 1. Northbank Avenue, where we had our shelter, was actually a radio station from 1940 and two Polish officers lived there. I remember them being there but never seemed to wonder what was going on……

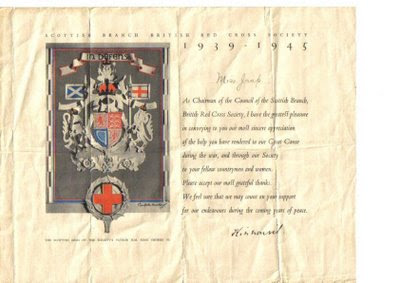

During the war years I used to knit scarves and socks for the Red Cross who passed them on to the Forces. Some knitters put their name and address on the finished item but I never did. This is what I got from the Red Cross thanking me for my war effort.

The next thing that happened was that there was a great fear of German planes coming over and bombing our towns. Clydebank was thought to be in danger because of the ship-yards there, so it was decided to move all the children away to a safer place - in this case - Kirkintilloch. Thousands of them arrived in our town, with their mothers, but no fathers - they had to stay and carry on with their jobs. They were brought to the Town Hall, carrying bags with clothing, and with labels pinned on their coats showing their names and addresses back home in Clydebank. The people of the town had to report to the Town Hall to be allocated a child or children. My mother was given a family of three - Peggy was about twelve , Jack ten, and William five years old. We had no spare beds, so my mother put a mattress in a corner of the living-room, on the floor, and all three slept there. After a week, their parents came to visit, and decided to take them back home. What I remember particularly is they had not lived in a house with a BATH before. Gradually, many others went back to Clydebank, as there had been no bombing at that point though some families stayed in Kirkintilloch permanently.

We lived in Northbank Avenue - just a small avenue of six houses, which had all been built by Mr. Fletcher, the local builder. He lived in the largest one, built on a steep hillside, which gave him a big cellar. When war came, he decided to make this cellar into an air-raid shelter, for all the Avenue people, and one other lady. He fitted it out with comfortable seats, a couple of bunks, lighting, heating, tea-making facilities and even a toilet. The air-raid siren was on the roof of the Police Station, in the centre of the town. It made a loud wailing sound, which could be heard for miles, first a warning sound, then the ‘all-clear’ if the danger was past. So, throughout the war, we went to the shelter when the siren sounded, always at night, and having to get out of bed and get dressed. Our house looked away over to Bishopbriggs, where there were anti-aircraft guns, which would fire at enemy planes. You know there is a saying “What goes up must come down“. During air-raids it was unsafe to be out because shrapnel from the guns would rain down - great lumps of jagged metal - these would be lying about the streets the next morning. I wish I had kept some, just for interest. I never knew of anyone getting hurt by the shrapnel, but my father’s friend had a pony and trap, and a piece came through the roof of the shed and killed the pony. In 1941 Clydebank was bombed two nights running, 439 planes came over and dropped 1000 bombs. The town was a ruin, lots of people killed. Kirkintilloch Fire Brigade went to help put out the fires, some of which still burned after a fortnight. Grandpa Green’s father was a bus-driver at the time. And driving in that area. One bomb went down the funnel of a ship lying in the Clyde - but it didn’t explode. Of course, we were lucky to be safe in our shelter, but no sleep for the noise of gun-fire etc.

[John adds: “One of our uncles, a joiner to trade, was a part-time member of the local Fire Brigade at the time of the Clydebank blitz. He couldn’t cope with what he saw there, and that was the end of his time in the Fire service.”]

[John adds: "Jean my wife lived near the docks in Glasgow and remembers the night the bomb went down the ship's funnel. She had been evacuated, but this was one of the occasions when she was spending some time at home. The whole area had to be evacuated, and she and her family spent the night in a close in Sauchiehall Street opposite Kelvingrove Park."]

Then there was the BLACK-OUT, no lights allowed to shine out of windows or doors, everywhere heavy curtains drawn at night, and NO STREET LIGHTS, can you imagine it? Cars had very faint lights that would not be seen from above, by planes, and no name signs on roads.

Just learned this very interesting fact recently from a booklet John gave me.

The Fletcher home, at No. 1. Northbank Avenue, where we had our shelter, was actually a radio station from 1940 and two Polish officers lived there. I remember them being there but never seemed to wonder what was going on……

During the war years I used to knit scarves and socks for the Red Cross who passed them on to the Forces. Some knitters put their name and address on the finished item but I never did. This is what I got from the Red Cross thanking me for my war effort.

Another way people helped the war effort was by digging up their lawns

and planting vegetables to help feed themselves when food was scarce. I

remember my father digging up one of our lawns.

This is a photo of Rita and John probably in 1943. He is in the uniform of the ATC (Air Training Corps) a voluntary organisation for boys not old enough for the armed services.

The war lasted for six years so I was quite grown-up when it was all

over. John was in the Royal Air Force for two years. Young men on

reaching a certain age had to do National Service.

This was Grandma’s war. Nothing bad happened to our family. Sadly my mother’s Canadian cousin, who was a Spitfire pilot, died.

And life would never be the same for lots of people…….

This was Grandma’s war. Nothing bad happened to our family. Sadly my mother’s Canadian cousin, who was a Spitfire pilot, died.

And life would never be the same for lots of people…….

-o0o-

No comments:

Post a Comment